WELCOME TO

DOPPELGANGER SCRATCH

Photography by Beatriz Pereira

CONTACT US

Feel free to get in contact with is through any of the platforms below

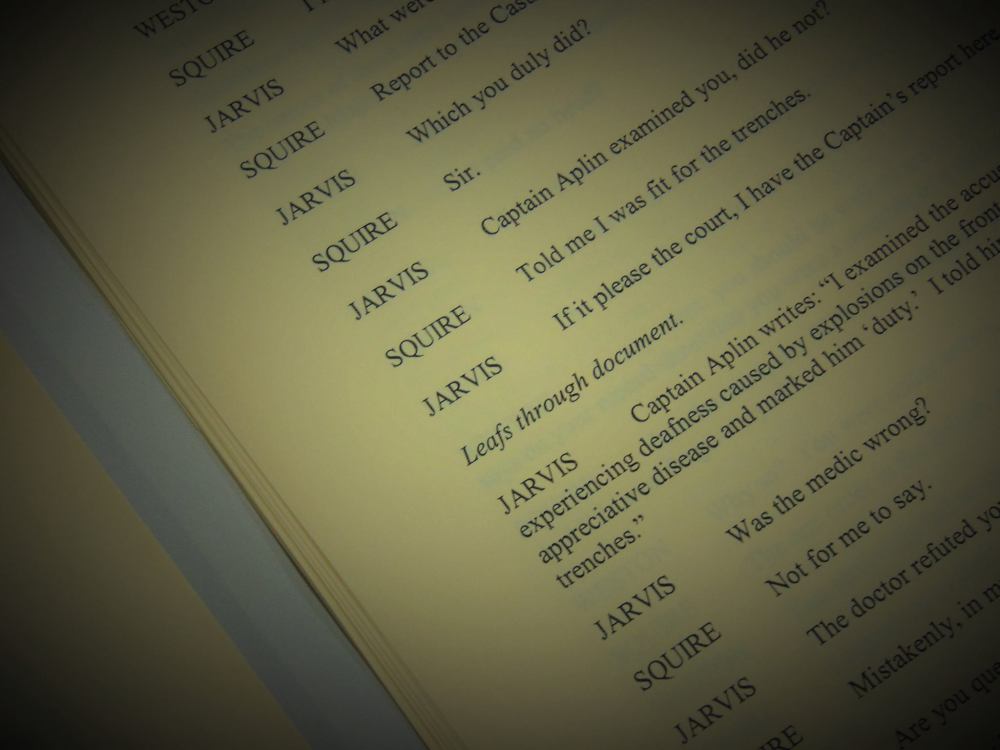

Shot at Dawn Preview by Brad Gyori

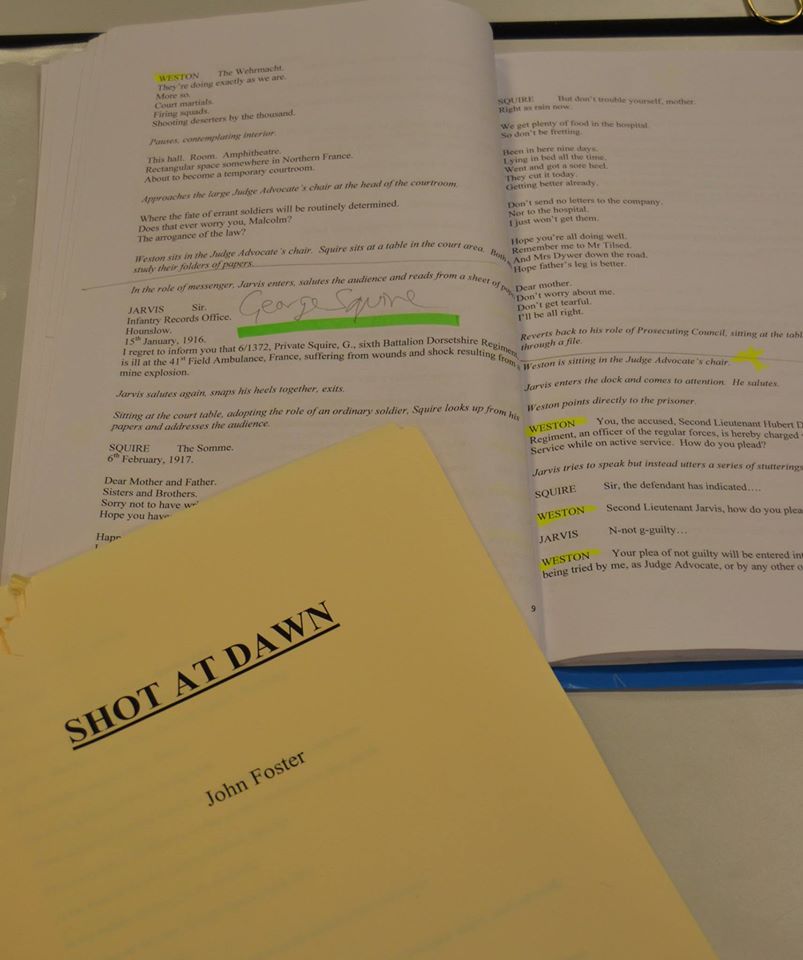

In his latest play, Shot at Dawn, John Foster is working on a bigger canvas and tackling a new genre. While he often specializes in psychological thrillers and gothic mysteries, Shot at Dawn is a historical drama, though hardly a traditional one. This is a John Foster play after all.

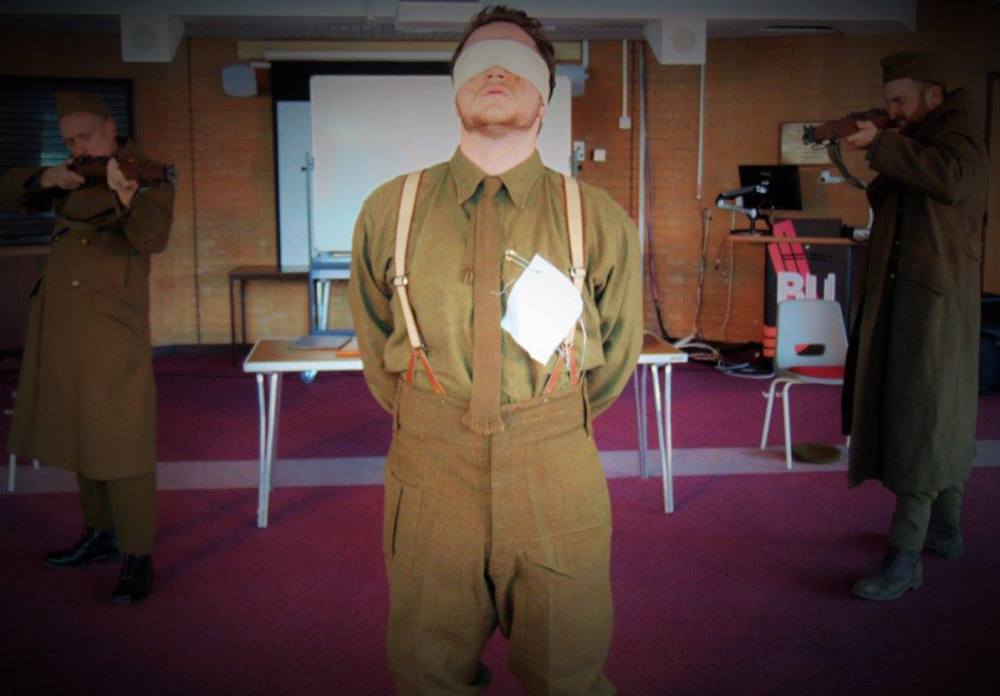

Practically speaking, this WWI tale is a three-hander with a trio of talented actors performing on a single stage, but director Kristie Davis embraces the complexities of Foster’s Swiss Watch plot, challenging her cast to take on multiple interchanging and interlocking roles. Meanwhile, inspired staging, lighting and sound design transport the audience from the trenches of the Great War to a military courtroom to a remote firing squad.

Practically speaking, this WWI tale is a three-hander with a trio of talented actors performing on a single stage, but director Kristie Davis embraces the complexities of Foster’s Swiss Watch plot, challenging her cast to take on multiple interchanging and interlocking roles. Meanwhile, inspired staging, lighting and sound design transport the audience from the trenches of the Great War to a military courtroom to a remote firing squad.

Shot at Dawn has a lot on its mind. It explores issues of class and rank. Are officers entitled to more justice than enlisted men? And it asks hard questions about the nature of courage, sanity and compassion. Naturally, things get gritty, but you can also expect some of the playwright’s other trademark strengths, moving reflective passages and powerful dramatic conflict.

All three actors are standouts, chameleons that masterfully negotiate dramatic switchbacks as they change roles from judge to executioner, from lawyer to defendant, from predator to prey. Particularly moving is the final scene where a young private, Adam Jessop, rages against an unbending judge played with both sympathy and resolve by Andrew Wheaton. The lawyer grilling Jessop is, Zach Powell, the same actor who earlier plays a shell-shocked character on trial for his life. This shape shifting lends an intriguing double-edged quality to his performance.

Up to this point, the writing and direction have challenged all three actors to maneuverer through the contortions of performing multiple roles, but now, the play has a different trick up its sleeve. In this last scene, the three leads are finally trapped in fixed roles. There will be no more shape shifting, no chance of escape. The plight of Jessop’s character is especially poignant.

This young man has seen every one of his friends slaughtered in battle and has survived it all only to be targeted by his fellow soldiers. There is nothing he can do to avoid this fate. There is no other space or time or persona he can shift into. A sleepwalker who has fallen into the gnashing machinery of total war, he is trapped. Jessop makes the most of this claustrophobic moment; planting his feet firmly within the tiny circle Foster and Davis have drawn for him. The rifles are aimed and we see that, no matter how he swaggers, rants or pleads for mercy, there is nowhere left to hide.

Shot at Dawn Preview by Jim Pope

The brightly lit and airy student centre at Bournemouth University might not seem likely to be a strong setting for John Foster’s World War One drama, but such is the power of the script and the quality of the acting in this dress rehearsal, that I was very quickly totally absorbed in the narrative playing out before me.

The minimal production (just costumes for the actors, plus some background sounds and occasional eerie green lighting) works very well, because all the work is done in the audience’s heads, triggered by line after line of nerve-shredding intensity. The firing squad lines up, aiming their rifles directly at the audience (so it feels), and we hear the soldiers talking about the realities of this execution: if their bullets don’t do the job, ‘the officer will finish him.’ This is not neat and tidy (the executed man will ‘wet his bags’ at the point of death), and this is not just – we see and hear Private Georgie Squires arguing and pleading for his life, which he knows will be taken from him because of one fatigued, disoriented disappearance from the battle field. Even after a career of ‘exemplary’ service, the error of judgement cannot be forgiven. Squires berates the court martial for its insanity, and we feel it.

Foster’s script is clear, clean and direct – you feel the hopelessness of Squires as he loses his temper, tries to reason, gives in, and recites a tearful final letter to his mother that he will never send. As he challenges the prosecution’s ‘evidence’ he shouts , ‘What would you know? Ever been in a battle?’ But it will all be in vain: absent without leave gets you shot at dawn.

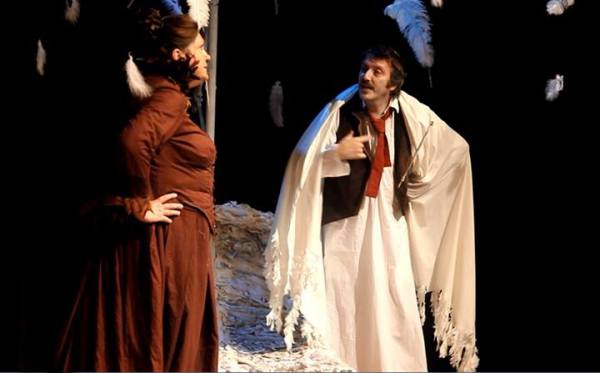

The One Gentleman of Verona — Dorian Gray goes Latin

Over the last few days I have been in Verona working on a new version of my free adaptation of THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY. There have been many intense and highly stimulating discussions with the director, Catia Pongiluppi, the producer, Stefania Allegrini, and the designer, Angelica Dal Ben. The production is the brainchild of Stefania, who was excited by Charmaine Parkin’s production of the play in Bournemouth and London last year, proceeded to translate the two-hour text into Italian, and then approached Catia with the project.

Catia, who directs opera and theatre in Verona, is a very exciting director to be working with, I really like her approach and ideas, and her passion.

For the playwright one of the great strengths of theatre is to see work performed in different versions by different people, and to learn from the diversity of interpretations. This hardly ever happens in television or film. I am very excited by this production and can’t wait to see how it evolves over the coming months.

Falling into Echoes – SHOT AT DAWN on tour

Fifteen months ago a play of mine called SHOT AT DAWN was performed in the council chamber of Bournemouth Town Hall as part of that year’s Bournemouth Arts Festival by the Sea. The council chamber is a beautiful evocative interior which had once been a theatre and in another period part of a hotel. It is also said to be haunted. The enclosure lent itself perfectly to the play’s main setting, an improvised courtroom. The play is set in World War One and concerns the court martial and execution at dawn of soldiers charged with cowardice and dereliction of duty. These soldiers were usually suffering from shell shock or PTSD, a condition known about then but not specifically identified. Some soldiers were shot for quite minor offences – insubordination or for visiting their mates in an adjacent encampment without leave of absence but with no intension of absconding.

Because the court martials took place in the field as the British army advanced across France, hearings took place wherever available – in a tent, a hut, any building which had survived the bomb blasts. A temporal space was all that was needed for the average trial which lasted twenty-minutes for squaddies and one hour for officers.

Although not a site-specific drama in the purist sense since the town hall council chamber was imagined as a derelict building somewhere in Northern France and not an actual location where this would have happened, the venue itself was a strong draw for audiences and we were sold-out for the three-night run. Indeed you could say that the echoey council chamber was a character in the play, with its weight of the past bearing down atmospherically upon the proceedings. The walls seemed to speak of the past, of its agonies and injustices.

The new production of the play, produced by Carol Maund, who originally commissioned the play for Bournemouth Arts, and again directed by Kirstie Davis, once more embraces the idea of place as much as story or performance by touring towns in Dorset – Dorchester, Blandford Forum, Bridport and Poole – and mounting the production in non-theatrical venues: a shire hall, an old courthouse famed for the trial of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, a corn exchange, a guildhall. These enclaves seeped in the past bring a compelling mood and atmosphere to the piece, but a powerful sense of realism and an almost telepathic aura born from the veins of the buildings. These were the places frequented by our forebears, these walls also looked down upon them.

As rehearsals begin this past week, it is fascinating to watch the process by which the play is brought to life again. From the playwright’s viewpoint, one of the strengths of theatre is to see a play mounted in different versions and what you can learn from such a diversity of production, since every production and every performance is different. With two new members of the cast, it is intriguing to see what they bring to the interpretation, the attitudes they imbue the characters with, the emphasis and subtle shifts of meaning they bring to the text. The trio of performers – Andrew Wheaton, Zach Powell and Adam Jessop – play multiple roles identified by their multifarious performances and by the military caps they are wearing at a particular moment. The narrative weaves between naturalistic and non-naturalistic moments in action which veers from the courtroom drama of the court martials to breakout sequences in the field.

One of the main themes of the play is the class differences, particularly in the way squaddies were treated and the much more considerate solicitudes extended to officers, who were invariably represented by lawyers while the rank-and-file soldiers were not. Of course, nobody at all should have been shot for whatever reason, but it is fascinating to contemplate how class divisions drove certain men towards the firing squad and others not. These brutal and unnecessary executions added to the already obscene piles of death on the battlefields and the mud-clogged trenches, overrun by rats and frogs. A disturbing and depressing fact is that many soldiers, however personally sympathetic towards individuals, were not against the court martials and executions, did not disapprove of them, and regarded such action as just desserts.

The Ballard Of Martha review by John Foster

Last month I was fortunate enough to see a preview of The Ballad of Martha Brown, Angel Exit Theatre’s brilliantly stimulating and engaging account of Martha Brown, the Marshwood Murderess, whose death by hanging in 1856 made her the last woman to be executed in Dorset. The play, on tour, was performed at the Shelley Theatre, Bournemouth, on Wednesday this week.

This Catherine-wheel of a production was exhilarating, gripping and moving, with an enviable strain of laconic humour, much of it black, in the bleakest of dramatic circumstances, giving the piece a tantalising Mack-the-Knife cabaret quality, which combined humour with the horrific. The show was shot through with dark sardonic irony. Using direct address, often wry and gently mocking of the audience, the action involved and indeed embraced the audience, making us very much part of the experience. Even before the play commenced, the actors, in costume and in-character, mingled with the audience in the theatre foyer and bar, chatting to us. With songs, accordion and fiddle, the lively action sometimes broke into a dance and the play itself was like a provocative dance of death between the characters.

The set was almost a character in its own right. Powerfully designed and structured, with the noose Martha was destined for suspended over the whole proceedings, the set provided nooks and crannies for the ensemble to hide within and impishly pop out from at any given moment. The effect of this was amusing yet sinister. The entire production was exuberant and compelling, marvellously directed, orchestrated and performed, especially Lynne Forbes in the highly exacting and beguiling role of Martha Brown. She carried an intense sense of doom with her very presence, seeming to foreshadow her own death.

I think the greatest compliment I can pay is that I didn’t want the play to end. I wanted more and even more of this exotic, entrancing and diabolical tale. Here the cliché of the theatrical experience was accurate and true. There were, however, some shortfall in concept and scripting.

A problem for the narrative is that Martha’s Brown’s story, although tragic of course, is unexceptional and predictable. That is part of its power, but this is the kind of story we are very familiar with and we know the outcome will be bleak. As a piece of social commentary, our horror is muted by familiarity and distance.

The real interest in the story is the moment of collision between Martha and her increasingly brutish young husband and his ensuing murder by Martha. Brilliantly staged with powerful physicality yet audacious stylisation, the production successfully plays on the growing inevitability of this scene in a kind of downward spiral, yet this does not diminish the audience’s need and desire to be surprised, for there to be a few more twists and turns, for the narrative to be less obvious and foreseeable.

The remainder of Martha’s journey to the gallows also treads a familiar path. We know with acute foreboding that all will end badly and the play skilfully plies us with this cruel foreshadowing. However, it is difficult to see why the early parts of Martha’s life should detain us at such length. A true story doesn’t necessarily make for an interesting story. Much of this backstory could have been recalibrated at a later stage in the narrative rather than the rather plodding linear biographical development we were offered.

I also had a problem with the relationship between Martha and Tom, evidently so much in love in the first act, yet with Tom turning drunk and violent very suddenly at the beginning of the second act. The amelioration of Tom’s disaffection needed more astute delineation. As such, the effect was superficial – a man tired of his older wife falling for a younger woman. An old story, but here in need of refreshing with more complex characterisation and a greater sense of the gradual destruction of the relationship. Tom’s character was one-dimensional and he seemed to possess mutually exclusive characteristics – innocent and loving towards Martha on the one hand, vicious and sadistic towards her on the other, with no real sense of the souring of their love and the process of alienation. Although well performed, Tom remained more stereotypical than archetypal with little feeling of an inner life.

The material of the play suffered from its fidelity with fact, the historical truth, but in a sense this also became a strength in the Martha’s Brown tale becoming a metaphor for the universal deprivation and vicissitudes visited upon many poor working rural people of the time. Little narratives popped up during the play – one particularly haunting moment was when a mother confessed to drowning her eight children – mini narratives amusingly suppressed on the basis that ‘this is not your story, this is Martha’s story,’ yet effectively broadening the thematic scope of the play and the social commentary it contained so that Martha’s tale becomes a symbol of general poverty, social division and oppression.

Despite reservations concerning the narrative, I loved this play and its highly spirited production. There should be much more theatre like this, willing to experiment, innovate and utilise the breadths of theatrical form. This was a delicious evening, which the audience lapped up, and made for a very precious, special event.

An interesting inclusion in the narrative was the presence of Thomas Hardy who, at the age of sixteen, witnessed the execution of Martha Brown outside Dorchester prison. Apparently Hardy drew inspiration for Tess of the D’Urbervilles from Martha Brown’s history, but his sensuous description of the hanging, the slowly swinging, wheeling body of Martha, attired in a long tight black silk dress, was curiously and disturbingly erotic.

The Ballad of Martha Brown was written by Amy Rosenthal, Tamsin Fessey and Lynne Forbes. The play was directed by Tamsin Fessey & Lynne Forbes.

Catch it if you can.

John Foster

The Ballard Of Martha review by John Foster

Both the summer festivals – Bournemouth University’s Festival of Learning and Poole Arts’ LitUp Festival of Words – which each hosted a performance of our Doppelganger play about Robert Louis Stevenson, The Weevil in the Biscuit — are now over, although I don’t sense any impending robberies á la Dylan in the somewhat flat late July aftermath. Doppelganger completed the first leg of its tour of The Weevil in the Biscuit last Friday evening with a final performance of the play at the evocative venue of Scaplen’s Court in Poole as part of the excellent Festival of Words, the brainchild of Matt West, Literature Officer of Poole Arts.

This is Doppelganger’s first foray into touring proper. We have undertaken short limited tours, such as last year’s Festival of Learning production of The Murder Wife, when we performed at the Bournemouth University Festival of Learning 2014 and Chaplin’s the Cellar Bar in Boscombe. In earlier play productions we have visited the Lighthouse Poole, The Winchester Bournemouth and the Rex Cinema Wareham – but these tended to be one-off gigs rather than a part of a tour. This is the first time we have mounted a sustained tour and it has been stressful and exhilarating in equal measure. Thanks to the superb occasional capabilities of our producer, Nick Taylor and our publicity manager, Felicity Cromack, part one of the tour has gone relatively smoothly. As always, there have been one or two little local difficulties which will be ironed out before we renew our run of the play in late October and early November. This new venture for Doppelganger has proved to be a steep learning curve in certain areas.

We have been lucky enough to have received Grants for the Arts funding from Arts Council England, which has made it possible for the tour to happen. An early decision to divide the tour into two time periods means that we now break for the summer and resume the tour in October. This is because of the unlikeness of securing a strong audience presence during the summer months. Even in July we have been teetering on being out-of-season and audience numbers have been variable. We enjoyed a 150 sell-out audience at Bournemouth University and the Festival of Learning, but struggled more to achieve audiences at Chaplin’s the Cellar Bar, despite great enthusiasm from audience members. Sometimes audiences were quite thin in numbers, but always positive about the production and often wishing to spread-the-word and promote the production to friends and work colleagues.

Our final performance at this point in the tour at Scaplen’s Court was brilliant, with Mark Freestone as Robert Louis Stevenson and Elaine Harry as his American wife, Fanny, really excelling themselves and were absolutely terrific, a great climax to this part of the tour. Despite the dreadful, stormy night we had a good sized audience and a lively Q&A afterwards. Most performances have been followed by Q&As and they have been extremely engaging and a great way of enabling audience participation. Doppelganger also offered two workshops at the Festival of Words which proved very successful – one on screenwriting and the other on radio drama was particularly successful and well received by the participants, many of whom requested further workshops on the art and craft of writing radio drama. I thoroughly enjoyed our engagement with the Festival of Words, both the performance of the play and the two workshops were very stimulating experiences for us all.

One of our ambitions is to discover new audiences for our productions and to perform in non-theatrical venues not normally associated with fringe theatre. This is a great challenge and we have had mixed results on the first part of our tour. There is a lot of thinking to do on how we take theatre to people who are not especially interested in it and even alienated by it. The impact of live theatre can sometimes be disturbing for an audience used to film and television. A few audience members used the word ‘intense’ to describe the play and its performance. To me this is a compliment, although one young woman found that it made her feel nervous and intimidated, especially in the moments where the actors directly addressed the audience. But theatre is up-close-and-personal where the perspiration and the spittle is real and is very different from the staid rather fusty image of theatre some people imagine it to be. Our objective is to breakdown that impression and show people unacquainted with theatre just how dynamic and exciting it can be, offering a unique experience and a level of inclusiveness impossible for film and television.

The highly talented group Wikkaman preluded our first wave of performances with a beautifully written and performed song which related closely to the play and I feel added much atmosphere to the production. I find myself surrounded by brilliance on this production and my thanks go to Charmaine K Parkin for her inspired direction, Robert Wallis for his wonderful stage management which was totally lacking in melodrama, our amazing and extremely hard-working producer and publicity manager duo, Nick Taylor and Felicity Cromack. We have also been very fortunate in having a very lively, enthusiastic and inventive intern with us on the production – Lauren Stevens, whose cheerful presence and dedicated work has served us well. And much gratitude, of course, to the actors – Mark Freestone and Elaine Harry – for their exceptional and compelling performances.

Now for a lazy August as we recover and prepare for Weevil-2. In all, our tour consists of visits to ten venues and fourteen performances of the play, with aftershow Q&As and creative workshops along the way. In October and November we will be mounting eight performances in seven venues, travelling between West Dorset to East Dorset, the Test Valley and with still a smattering of performances in Bournemouth, so if you missed Weevil the first time round you can catch up with us in October – there’s no escape.

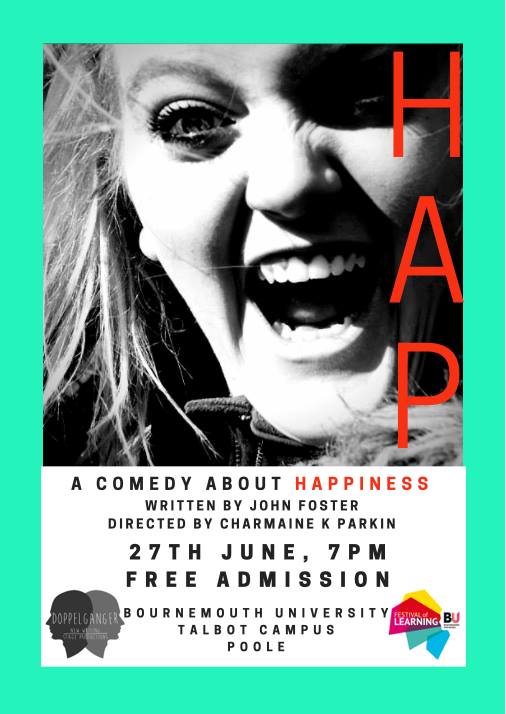

HAP: preview by Anna Marie Jaio-MorGan

John Foster’s innovative new play offers audiences a refreshing insight into the perceptions and thoughts surrounding the issues of mental heath through a comedic interaction and conflict of opposites; depressive Dr. Martha Maples, played by Emma Loveday, and Nicola Stringfellow’s equivocally happy ‘HAP’. The acting throughout the performance is strong and flows freely without interruption, under the masterly direction of Charmaine K Parkin, drawing the audience into the world and unfolding conflict in a quest for understanding.

Loveday’s Doctor Marples is a comedic dark delight from her opening ‘self help’ and ‘positivity’ routine to her endless search for the negative cause and traumatic source of Hap’s endless joy. Her defensive demeanor, constant struggles of patience and cold clinical delivery are expertly maintained and expressed throughout and characterise the main perceived stereotype of mental health practitioners with accuracy. Her gradual journey from defensive dismissal and passive aggressive security to an understanding and respect for a condition she had first believed as an act is handled well. There are a few drops in characterization and inconsistencies towards the end which don’t line up to her earlier professional model nor the role of a mental health practitioner, though I suspect this is due to the desired plot outcome as opposed to the acting, which is superb.

Nicola Stringfellows ‘HAP’ is an emotional rollercoaster of endless energy and boundless delight with even her struggles to adopt an alter ego being hilarious from the outset. Her entrance onto the stage makes her memorable from the outset and her exit and reappearance in order to approach the doctor in a seemingly ‘non threatening’ manner is one of the highlights of the first half. Her endurance in maintaining the role and consistently staying within character is both remarkable and captivating keeping the audience enthralled and sympathetic to her plight, even if they are a bit jealous.

The opening choice of backing music for the audience’s entry is a clever introduction to the idea of a ‘stoned’ world in which drugs and specialist treatment is seen as the ultimate answer for something that cannot be categorized or placed within a box; and whose prevalent message is seen to be so strong that even Hap is driven to resort to it’s promise as a cure to her joy. As a strong influence to the performance to come, it was complimentary in it’s message but sometimes overpowering in its delivery; making it difficult to focus on both the lyrics and the powerful opening sequence of the superficial nature of self help techniques at the same time.

The minimalistic set adds to the tension in firmly establishing the differences between the conflicting emotions and mindsets of the two characters. In particular when Hap attempts to breach and invade the doctor’s fortress and defenses by both removing and examining the pill boxes and bringing the chair into closer proximity to the desk we see how fragile and sensitive the defenses actually are.

Throughout the performance there is the unspoken question of deception; of the truth being hidden behind a façade of emotion. The constant need to play, perform and be something that you don’t necessarily believe in, desire or feel comfortable expressing, in order to be socially and culturally acceptable to the people and authorities round you. This mindset is brilliantly revealed in the doctors poignant line “Don’t we all wear masks?” making the line between the truth, performance and perception a virtual illusion that cannot be argued one way or another.

Likewise the perceptions and views of happiness and its affect on people’s attitudes are handled well. The performance slowly unfolds and extracts each layer of the categorization of joy revealing it to be a complex emotion which is viewed primarily as a threat and an inconvenience to the reality of pain and suffering, selfish in its pursuit of the unattainable and its intrusion upon others lives. The performance comes to its resolution by presenting both as the two sides or personas of human nature that cannot be complete without the other.

The presentation and portrayal of this resolution is a little loose and lacks plausibility. Several plot points within the first half of the performance offer the possibility of a twist ending revealing Hap as the personalization of a long repressed emotion in the doctor’s conscious. This could be seen as both an acceptance of herself as a combination of both emotions, and justified as a contradiction of the negativity surrounding the perceptions of mental health. Instead the decision to pursue a relatively mainstream and predictable ending through a switch from the professional model of Doctor and patient to that of a closer proximity leaves the earlier foundations of characterization distant but also leads to the audience becoming a little disconnected from the world of the play.

After watching excellent and groundbreaking past performances by Mr. Foster, I left the theatre with the several questions and reflections to pursue.

HAP — FREE performance — Monday 27th June @ 7 pm

Tickets should be booked by:

CLICKING HERE